WCERE2018: What are the lessons learnt from avoiding day zero in cape Town, South Africa and what are the economic and behavioral tools that can help us prevent other types of environmental crises? A pre-conference session on Economic instruments for water-scarce cities on June 25th addressed these questions.

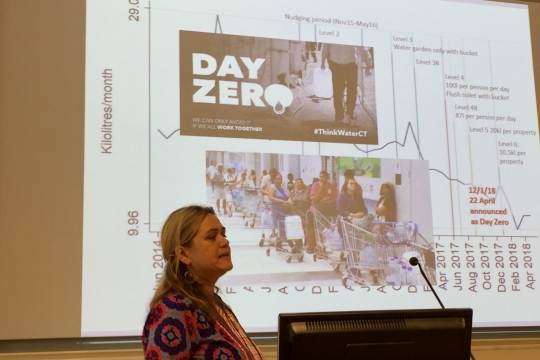

The news that around 4 million citizens of Cape Town could be without water as “Day zero” approached made the headlines across the world in January 2018. Martine Visser, Professor of behavior Economics at University of Cape Town describes this as a time when ‘academics became rock-stars’. Her team´s work on various efforts by the city of Cape Town to encourage voluntary water saving behavior amongst residents of the city, attracted global media attention.

Visser has worked closely with Cape Town’s city officials over the last couple of years to develop a response to the crisis. Her work on behavioral nudges to encourage household water saving has fed directly into the city’s own strategies and has shown that the right types of behavioral messages sent to households can be effective in reducing water use. Social recognition of water conservation efforts by households, social comparisons and appeals to the public interest in water conservation was found to be more effective in inducing behavioral change than providing information of the personal financial implications of water savings.

‘Four years ago, richer households were drawing much greater volumes from the municipal water system than poorer households. But in recent months, as restrictions have tightened, we see a dramatic change in consumption among the higher income households, while lower income groups have always had rather low levels of consumption’ says Visser.

Haileselassie Medhin, Director of the Environment and Climate Research Center at Ethiopian Development Research Institute opened the pre-conference session, talking about the role of environmental economics’ capacity for improved resource policies. Medhin said that many low-income countries are very ambitious with their national strategies for sustainable development and mentioned Ethiopia’s ambition to become a lower-middle income country by 2025 with a low carbon strategy.

‘ Researchers need to make sure that what we do really respond to policy needs. That way politicians will always be interested in what we do,’ said Medhin.

Dale Whittington, Professor at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, put the experience from Cape Town and economic incentives for sustainable water use in a global perspective. He mentioned that Sao Paulo in 2015 faced a similar “day zero” and there are at least 11 other cities around the world that are currently facing similar problems of water-scarcity.

Since pricing of water is important for long-term demand, Whittington continued to talk about Increasing Block Tariffs (IBT), which is the most widely used pricing scheme for municipal water use. Whittington explained that although the ambition with IBT is to cross-subsidize the water use of poor households that are assumed not to use a lot of water, by charging rich households (who are assumed to use more water), IBTs actually do not target the subsidies effectively.

‘ IBT’s are intended to help the poor, but in fact they don´t’ said Whittington.

Whittington mentioned three potential ways forward for policy makers to address the problem with IBTs. First, one needs to ensure that the poor actually fall into the subsidized “block” of consumption. Secondly, the connections of poor households can be subsidized to ensure that they have access to affordable, potable water services. Third, provide free or subsidized water from public taps as a safety net for poor households.

‘Of course, the appropriate policy mix for these three pro-poor instruments will depend on local conditions, but most importantly: Policy makers need to make sure there is water in the pipes’ said Whittington.

There are too many existing strategies relying heavily on expensive and sometimes ineffective infrastructural investments, but not including plans of how to encourage households and businesses to conserve water. Hopefully the successful water-saving campaigns and bahavioral insights from avoiding Day Zero in Cape Town will guide policy makers in other water-scarce cities world-wide to use the full tool-box of environmental economics to create sustainable water access.

Presenters and panelists in the session were:

Martine Visser, Professor University of Cape Town

Dale Whittington, Professor University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

John Joyce, Chief Economist, Swedish International Water Institute

Ariel Dinar, Professor University of California Riverside

Michael Hanemann, Professor Arizona State University

Moderator: Gunnar Köhlin, Director Environment for Development, University of Gothenburg

Further reading: Beyond day zero in Cape Town- economic instruments for water-scarce cities