In January 2018, the South African city of Cape Town came within three months of running out of municipal water, following the worst drought in over a century. ‘Day Zero’ was the day when water managers would initiate emergency rationing measures, shutting off water to homes and businesses outside of the central city. Residents would have to collect 25 litres of water per person, per day, from distribution points around the metropolis. The city used various measures through the course of the three-year drought to encourage water-saving behaviour amongst Capetonians. Researchers from the Environmental Policy Research Unit (EPRU) at the University of Cape Town worked with the city to track how effective these were, and also rolled out a series of behavioural ‘nudging’ experiments to help drive down water use.

The lessons learned from this apply to other municipalities facing the twin challenges of population growth and resource constraints, particularly as climate change increases the likelihood of extreme weather events.

What are the challenges?

With Cape Town’s current growth, demand for water is expected to outstrip supply within a decade, without the added pressure of extreme weather events like this drought.

The historic development inequalities also show themselves in the water system. With a population of about 4 million, people living in formal housing use two-thirds of the city’s residential water (66 percent), according to a recent report by the African Centre for Cities[1], while almost one-third (1.5 million people) can’t afford to pay for water. Some 180 000 households live in informal settlements and don’t have running water in their homes, meaning they must collect water from communal standpipes and share outside toilets.

In terms of managing its responsibilities around water service delivery, the city has to encourage water saving behaviour amongst higher-using citizens, while meeting the service delivery backlog to those still waiting for water and sanitation in their homes.

The city uses a tiered block-tariff billing system to fund its water delivery. This system charges a relatively low price for the first basic units of water that people use, but the more a household uses, the steeper the price per unit. The income from the higher-priced water subsidises water delivery to lower-paying households or those who qualify for a free basic quota. This ‘revenue’ model has been criticised because it doesn’t incentivise a municipality to encourage lower consumption of a revenue-earning resource like water.

EfD is addressing the problem

Early in the southern hemisphere summer in 2015, before anyone knew that a drought was imminent or how bad it would get, behavioural economists at EPRU were already working with the Cape Town municipality to track residential water use. EPRU is a member of the Environment for Development (EfD) initiative.

EPRU director Professor Marine Visser and her team - including Johanna Brühl, Megan McLaren, Dr Kerri Brick, and Dr Samantha DeMartino - began running a six-month experiment through the summer, where they tested a series of ‘green nudging’ interventions, to see if they could encourage residents to voluntarily adopt more water-wise behaviour.

The experiment involved teaming up with the city to send a series of simple, positively-worded messages to households through the municipal billing system, all of which urged people to use water more sparingly. These messages went to 400 000 households in different income brackets. The economists then looked at how people responded to these sorts of interventions, and compared these results with the city’s usual efforts to encourage water-saving behaviour, such as the tiered block-tariff pricing system.

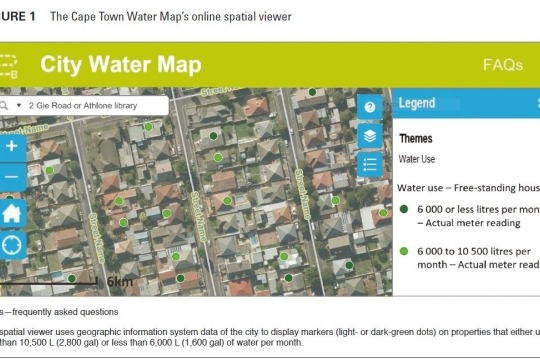

EPRU researchers then continued monitoring water use across the city as the drought intensified. At the same time, the city began instituting other measures to change water-use behaviour. They pushed up the price of water, and brought in increasingly tighter water restrictions, along with fines for those who flouted restrictions. The city also threatened to name-and-shame the worst offenders who flouted restrictions or to regulate their water use with water cut-off devices. The city also implemented a series of online communications efforts, including a Water Dashboard and the ‘Think Water’ website, which gave regular updates about dam levels, and gave information on how the public could save water.

The most important communication drive came with the release of the Critical Water Shortages Disaster Plan in October 2017. This is when the notion of ‘Day Zero’ eternal the public domain: a day when the city would implement emergency rationing measures should the dams run down to their last 13.5 percent. By January 2018, the city said that it was just three months away from implementing ‘Day Zero’.

EPRU researchers tracked how people responded to all of these measures over the course of nearly three years. The result of this analysis can now assist the Cape Town municipality to refine its policies relating to demand-side water management using evidence-based analysis. Visser says this is the kind of collaboration and thinking that needs to inform city-level policies around water and energy use, not only in a crisis situation or in Cape Town, but for other cities in the Global South.

Take-home messages, to support future policy

EPRUs take-home messages for city water managers, which researchers hope might inform future strategies and policies for how it engages with water users:

Rewarding water-wise behaviour: In the ‘green nudging’ experiment, researchers found that those families who opened their monthly utility bills and found a message from the city saying that they would have their names published on the municipality’s website if they cut their water use, were more likely to adopt water-saving behaviour.

Money doesn’t talk: Middle and higher-income households’ behaviour didn't respond much to water price increases, or the behavioural nudges that highlighted the high cost of excessive use, because wealthier people don’t feel the financial pinch as much.

Restrictions work: People responded quickly to water restrictions, such as bans on hosepipe use (people could only wash cars or water gardens using buckets), or insisting that private swimming pools be covered.

Online information and tools: People responded well to communications efforts such as the Water Dashboard and the ‘Think Water’ website which gave regular updates about municipal dam levels, and gave useful tips on how to save water.

Targeting the worst offenders: The city sent reprimanding letters to households that were using more than 50 kilolitres of water per month, asking them to lower their usage, and also threatened them with the installation of water cut-off devices. These families changed their behaviour in response, reducing their water use for up to seven months after receiving the letters.[2]

Clear, salient information: When the city released the Critical Water Shortages Disaster Plan in October 2017, and popularised the notion of Day Zero, this produced the single biggest water reduction during the drought.[3] Visser says that sharing clear, relevant information with people during times of crisis is key for driving behavioural change, particularly if it gives people a sense of what they can do to help resolve the problem.[4]

Which SDGs does this work tackle?

SDG 3: Good health and wellbeing

SDG 6: Clean water and sanitation

SDG 10: Reduced inequalities

SDG 11: Sustainable cities and communities

This research was made possible through funding and support from the Water Research Commission in South Africa, as well as SANCOOP (a collaboration between RCN Norway and the SA National Research Foundation), and the Environment for Development (EfD) initiative in Sweden.

Further information:

Ziervogel, G. 2019. Unpacking the Cape Town Drought: Lessons Learned. Africa Centre for Cities, University of Cape Town. Available: https://www.africancentreforcities.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Ziervogel-2019-Lessons-from-Cape-Town-Drought_A.pdf.

Brick, K. & Visser, M. 2018. Green Nudges in the DSM Toolkit: Evidence from Drought-Stricken Cape Town, Draft Working Paper, School of Economics, University of Cape Town. DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.16413.00489 on Research Gate and Academia.

Visser, M. & Bruhl, J. 2019. The Cape Town Drought - Lessons Learned About the Impact of Policy Instruments in Curbing Water Demand in a Time of Crisis. Draft Working Paper, University of Cape Town.

Booysen, MJ., Visser, M. & Burger, R. 2018. Temporal Case Study of Household Behavioural Response to Cape Town's ‘Day Zero’ Using Smart Meter Data. Water Research. Vol 149: 414-420.

Brick, K., Demartino, S., Visser, M. 2018. Behavioural Nudges for Water Conservation: Experimental Evidence from Cape Town, South Africa, Draft Working Paper, DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.25430.75848 on Research Gate and Academia

Sinclair-Smith, K. Mosdell, S., Kaiser, G., Lalla, Z., September, L., Mubadiro, C., Rushmere, S., Roderick, K., Bruhl, J., McCalren, M., Visser, M. 2018. City of Cape Town’s Water Map. American Water Works Association; Vol 110, Issue 9; p 62- 66 https://awwa.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/toc/15518833/2018/110/9

[1] Ziervogel, G. 2019. Unpacking the Cape Town Drought: Lessons Learned. Africa Centre for Cities, University of Cape Town. Available: https://www.africancentreforcities.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Ziervogel-2019-Lessons-from-Cape-Town-Drought_A.pdf

[2] Brick, K. & Visser, M. 2018. Green Nudges in the DSM Toolkit: Evidence from Drought-Stricken Cape Town, Draft Working Paper, School of Economics, University of Cape Town. DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.16413.00489 on Research Gate and Academia.

[3] Visser, M. & Bruhl, J. 2019. The Cape Town Drought - Lessons Learned About the Impact of Policy Instruments in Curbing Water Demand in a Time of Crisis. Draft Working Paper, University of Cape Town.

[4] Booysen, MJ., Visser, M. & Burger, R. 2018. Temporal Case Study of Household Behavioural Response to Cape Town's ‘Day Zero’ Using Smart Meter Data. Water Research. Vol 149: 414-420.