Stellenbosch, South Africa: An experimental geyser control device, which is operated via the internet a smart phone app, has the potential to cut household water heating by up to 30 percent without users noticing a change to their hot water use habits.

This is the preliminary finding of Dr Thinus Booysen, from the University of Stellenbosch’s Electrical and Electronic Engineering Department, following the first field trial to run outside of the Stellenbosch lab, after five years of developing the device.

Booysen was presenting his work at the University of Cape Town Environmental Policy Research Unit (EPRU) annual policy workshop, held this March. This year’s workshop focused on demand-side management of utilities, mostly at city-scale.

The geyser control device operates in three parts: a control box the size of half a shoe box is installed next to a geyser. In its pilot project form, the device then measures the water and electricity use in the geyser, and communicates the information via the internet to an online server that analyses the data using thermal models and other algorithms. The system is designed to allow the user - in this case, still Booysen’s team and the project’s first volunteer participants - to control the geyser via an app either on a computer or smart phone.

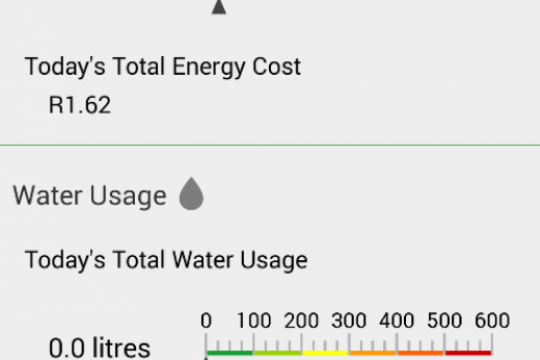

‘This allows you to log in anywhere in the world, to see what the flow rate and volume of used water is in your geyser, and what the temperature is,’ Booysen explains. ‘The smart app allows you to turn the geyser on and off remotely with click of a button. You can set the timer and the temperature. This allows you to design your own schedule control.’

The pilot project ran in six volunteers’ homes. Over the course of two weeks, the gadgets tracked the households' hot water use, and then allowed Booysen to apply customised heating schedules for each family. The programme was designed to shut off the geyser thermostat at strategic times to cut electricity use, while at the same time ensuring the household always had hot water when they were most likely to need it.

‘The information from the device is detailed enough to allow you to analyse your household’s behaviour: when you bath or shower, when you open a tap, anything involving the geyser,’ says Booysen. ‘It logs the time, the amount of litres and kilowatt hours used, and calculating the monetary cost of each bath or shower.’

Booysen then compared the water and energy use in these geysers with that of a control group where no schedule controls ran.

‘The households with schedule controls running on their geysers saved between 15 and 30 percent on energy during the test phase,’ Booysen reports.

While the field trial was very small, and didn’t show any conclusive findings on how the device impacts on user behaviour within the households, Booysen says the findings are promising, because most of the households reduced their energy use by 30 percent without noticing a change in hot water availability.

Taking the gadget to the market

It is a while before the device will be commercially available, but Booysen plans to market it through independent plumbers, who regularly replace geysers that are broken owing to bursts.

‘Here in Stellenbosch, for instance, one plumbers we consulted replaces about 10 geysers a day.’

He has also teamed up with the national Water Research Commission, which is rolling out 300 of these units in Mpumalanga.

Booysen is also in talks with the national utility, Eskom and the Department of Environmental Affairs for further pilot rollouts.

The device is expected to cost between R1 500 and R2 500, and shouldn't take a plumber more than half an hour to install. His team and Stellenbosch University have started a company for this purpose.

South Africa currently has about 5.4 million geysers in operation, have about 500 billion litres of water passing through them each year, and use an estimated R30 billion in energy annually.

The system also allows users to control the water supply, which is a way of avoiding burst geysers, something which Booysen says costs the country about R13 billion every year.

Workshop organiser, EPRU economics professor Martine Visser, said that this innovation illustrates the kind of novel work being done in research relating to demand-side management of utilities. Combined with efforts to nudge consumers towards changing their behaviour in relation to water and electricity use, these measures could delay by years the need for building expensive new infrastructure such as dams or coal-fired power stations.

EPRU is based in the University of Cape Town’s School of Economics, and Booysen is a research collaborator with this unit.